This is the text of a letter that was sent to DEEP in response to the issuance of their EV Roadmap, which was published last month.

November 12, 2019

Commissioner Katie Dykes

Deputy Commissioner Vickie Hackett

CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection 79 Elm St.

Hartford, CT 0610 DEEP.EnergyBureau@ct.gov

Dear Commissioner Dykes and Deputy Commissioner Hackett:

Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments in response to DEEP’s October 11, 2019 Notice and Opportunity to Comment on its draft Electric Vehicle Roadmap for Connecticut (draft Roadmap). The Connecticut Electric Vehicle Coalition (the EV Coalition or EVC) is a diverse group of clean energy advocates and businesses, organized labor, and environmental justice groups that support policies that will put more electric vehicles (EVs) on the road in Connecticut to achieve significant economic, public health, and climate benefits for our state.

The Connecticut EV coalition strongly supports the state creating a more strategic and ambitious strategy on zero emission vehicle (ZEV) deployment, one of several key strategies that will help the state tackle climate change, improve the public health and air quality, as well as create economic development opportunities for the state.

The EV Coalition appreciates the significant work that went into developing the draft Roadmap and looks forward to working with the Department to finalize a product that will serve as a useful guide for stakeholders and the State in equitably achieving transportation sector emissions reductions consistent with Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA) goals.

The transportation sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the State and responsible for the majority of smog-forming nitrogen oxide emissions. Connecticut will not achieve its GWSA commitments or achieve health-protective ambient air quality standards without significant electrification of transportation and reductions in vehicle miles traveled. To be effective, we believe that the Roadmap must strike the right balance between providing sufficient direction and avoiding over-prescription. The Roadmap should provide clear guidance to relevant market actors about expected roles and responsibilities and clarify both prioritization and timing for the recommendations in the document. At the same time, the Roadmap should eschew prescribing specific technologies, particularly given that technologies in the transportation sector are rapidly evolving and detailed specifications may become less appropriate over the duration of the Roadmap’s planning horizon.

With regard to prioritization, the Roadmap should clearly identify what needs to happen and when in order to ensure the state is on track to meet climate goals. The final Roadmap should include timeframes for its recommendations and identify high priority actions. As discussed further below, those high priority actions should include establishing aggressive public fleet electrification goals, including goals for transit fleets; conducting outreach to environmental justice communities to better understand local transportation and design electrified transportation solutions appropriate to each community; creation of a low-income EV rebate that is available for purchase of both new and used vehicles to help get more low-income residents into EVs; requiring the state’s utilities to develop electric rates that mitigate the impact that current demand charges have on deployment of fast-charging stations; recommending the adoption of EV-ready building codes so that all new construction is pre-wired for Level 2 EV charging; and recommending the elimination of the prohibition on direct sales of EVs in Connecticut, along with additional incentives for existing dealers to increase sales of EVs.

In prior comments, the EV Coalition urged DEEP to support its Roadmap with analysis of public charging infrastructure needs.1 We appreciate DEEP using the EVI Pro-Lite tool for this purpose in the draft Roadmap.2 DEEP should clarify, however, why the infrastructure need figures identified in the Roadmap using the EVI Pro-Lite tool differ from those provided in the final Governor’s Council on Climate Change recommendations,3 and include figures regarding the charging infrastructure needs for supporting 500,000 ZEVs in Connecticut in 2030. In addition, we urge DEEP to conduct sensitivities around key parameters (e.g., ratios of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to battery electric vehicles, distributions of battery ranges across the vehicle fleet, and availability of home charging) to better understand ranges of public and workplace Level 2 (L2) and DC Fast Charging (DCFC) plug needs for 2030.

Recommendations regarding Equity:

The draft Roadmap minimally addresses equity and environmental justice issues. We commend the acknowledgement to prioritize these communities, but believe the final Roadmap needs to go further. Connecticut’s current transportation sector favors the single-occupancy vehicle and trucks. Low-income and minority communities are often among the worst affected by air pollution caused by these vehicles, affecting their respiratory and cardiovascular systems, and the environments in which they live. Any further action to electrify the state’s transportation sector needs to address outstanding equity issues. While the policies noted below are addressed within our comments on the relevant sections of the draft Roadmap, we present them below for emphasis.

Connecticut should provide incentives for the purchase of older model EV’s in order to expand the option of an EV purchase to low and moderate-income households. Currently, our EV rebates only apply to the sale or lease of a new EV, this should be altered to include a low- income rebate applicable to both new and used EVs so lower-income households can take advantage of the program.

In addition, a minimum percentage of the benefits of electrified transportation programs should be established for environmental justice communities and state-identified Economic Opportunity Zones. In addition to the types of community-specific programs intended to identify electrified solutions to the specific transportation needs of these communities (discussed below), it may be appropriate to carve out a percentage of EV charging stations to be sited in environmental justice communities particularly in areas where residents shop, work, and attend school and church.

Since public transportation is more widely used in low-income and minority communities the Roadmap should also prioritize the need for more electric buses and school buses. Electric buses do double-duty – they reduce emissions and take cars off the road, lessening Connecticut’s road congestion problems.

With the proper mix of EV charging stations, EV rebates, and electric buses, we can ensure that the Roadmap properly acknowledges our most overburdened and underserved communities.

Recommendations regarding Public and Private Fleets:

While public fleets comprise only a small fraction of total vehicles in Connecticut, they are ideally designed for the state to truly “lead by example.” Studies show that increasing consumer awareness and familiarity with electric vehicles is important in influencing consumer purchasing decisions. Public fleets are one of the areas where Connecticut has the greatest direct control over the rate of vehicle electrification and creates opportunities to (1) increase direct EV driving experience with state employees and (2) increase the public visibility of EVs on our roads.

The current recommendation regarding the state fleet in the draft Roadmap—that the state “should consider setting targets for annual EV procurement for the state fleet, beginning with the goal of 5 percent of state vehicle in the first year”—is too weak: The state must set aggressive targets for electrifying public fleet vehicles.

Section 93 of Public Act 19-117,4 establishes several targets for EV deployment within the state fleet, which should inform the recommendation in the EV Roadmap.

- PA 19-117 requires, beginning January 1, 2030, that at least 50 percent of cars and light-duty trucks, and 30 percent of buses, purchased or leased for the state fleet to be “zero-emission.”

- In light of the state’s express policy of reducing GHG emissions and need to reduce other air pollutants, we urge the state to go beyond the minimums established by the legislature and adopt a policy of procuring 100 percent zero-emission vehicles where such vehicles meet the performance needs for which they will be used, leading to stronger public fleet commitments: with a goal of ensuring that at least 50 percent of the cars and light-duty trucks and 30 percent of transit buses in the State’s fleet are zero-emission by 2030.

- PA 19-117 expands the Department of Administrative Services (DAS) commissioner’s annual legislative reporting requirements to include a procurement plan that aligns with these state fleet requirements and a feasibility assessment for the state’s purchase or lease of zero-emission medium and heavy-duty trucks; and

- In alignment with the policy recommendation above, the feasibility analysis should be limited to the ability of commercially-available zero-emission vehicles to meet the performance needs required by the state. Any cost-benefit analysis should include estimated fueling and maintenance costs over the full useful life of the vehicle.

- PA 19-117 requires the DAS commissioner to study the feasibility of creating a competitive bid process for procurement of zero-emission vehicles and buses, and authorizes the commissioner to proceed if it would achieve cost savings.

- The final EV Roadmap should encourage DAS to explore this option, as well as the possibility of joint procurement opportunities with municipalities and other

Regarding DEEP’s recommendation to update and publish guidelines for the installation of EVSE at state-owned facilities and public and private EV charging stations, DEEP has the authority to do this, and we encourage the agency to move forward with this activity. Using its ability to “lead by example,” state-owned and operated facilities should adopt minimum percentage charging requirements for parking areas, and such requirements should be included within all state-funded school construction projects. DEEP promoted similar recommendations to be included within the state building code for new residential and commercial construction, and these recommendations should establish the floor for state-owned and operated buildings.

Connecticut should support and incentivize electrification of private fleets by: (1) working with private actors and utilities to provide advisory services to fleet owners considering electrification; (2) developing rebates or incentives to support associated charging infrastructure needs; and (3) requiring utilities to develop rate designs that mitigate the impact of demand charges.

Recommendations regarding EVs beyond LDVs:

We strongly support incentives to electrify MDV and HDV. Connecticut should look to New York’s truck voucher incentive program5 to identify ways to incentivize purchases of cleaner, electric MDV and HDV.

While we encourage including fleet conversion to EVs as part of the electric utilities’ distribution system planning, DEEP should recognize that private fleet charging depots will likely need to be sited on-premises, so it may not be possible to target underutilized electric distribution circuits for fleet charging depots.

Accordingly, we should not let load decisions be the sole determinant in driving our EV infrastructure decisions. While it is clear that there are potential benefits from using EVs as a source of load smoothing and energy storage, the EV Roadmap should prioritize infrastructure investment where such investments will meet EV demand and benefit local communities. The goal should be to develop a comprehensive plan for building out our charging infrastructure in a manner that maximizes the combined, total benefits of increased EV deployment.

As noted in the GC3’s December 2018 Report, some of the largest GHG reductions from the transportation sector are likely to be achieved by increased investment in EV buses6, and these investments will likely be in our largest cities and most heavily-trafficked transportation corridors. While these are likely not areas with excess distribution capacity, nevertheless this is one critical area where investment must be made. The electric distribution companies (EDCs) should provide location-specific maps where excess distribution capacity exists so they may be evaluated against other criterial that would support investment in EV charging infrastructure.

Additionally, EV time-of-use rates can be an effective mechanism for shifting vehicle charging to off-peak times when the distribution system may be otherwise underutilized.

With respect to the pending California Advance Clean Trucks rule, we encourage Connecticut to continue to develop policies that leverage California’s authority to enact stringent motor vehicle emissions standards and polices beyond the floor established by the federal government. We should not pause our efforts pending the outcome of the current federal lawsuit, but rather position ourselves to act quickly when the court rules in favor of California and Section 177 states, including Connecticut.

Recommendations regarding Expanding EV Charging Infrastructure:

- Building codes and permitting requirement recommendations

To encourage widespread adoption of EVs to meet Connecticut’s GHG reduction goals, policies must support the necessary infrastructure build-out to encourage consumer confidence with respect to “range anxiety” and support public education regarding EV technology. One critical component is expanding EV charging infrastructure, particularly in settings that vehicle purchasers cannot directly control (e.g., charging in public and semi-public/workplace settings, charging at multi-unit dwellings). It is also critical that new construction be capable of supporting EV charging infrastructure so that charging stations can be cost-effectively added as the need for them grows.

There is widespread consensus that the best time to prepare a location for the future installation of EV charging infrastructure is during the initial construction, rather than post-construction retrofitting. A recent analysis by Energy Solutions for the California Electric Transportation Coalition (CalETC) found that installing EV ready parking spaces during a building retrofit can save four to six times the cost of a standalone installation.7

The EV Coalition strongly supports the adoption of EV-ready building codes. DEEP must be an active participant in the adoption of updated building codes to ensure the necessary accessibility to EV charging as market penetration of EVs increases. To that end, DEEP should support adoption of EV-ready legislation through provision of templates for use in municipal building codes and zoning ordinances. The State has been presented with the opportunity to support EV-ready construction and has so far failed to act. The Code Adoption subcommittee of the State Codes and Standards Committee recently declined to adopt “EV ready” standards for new residential and commercial construction, citing increased cost and the relatively low number of EVs currently registered in Connecticut. This narrow view fails to adequately take into account the cost of building retrofits to accommodate charging infrastructure, as well as the clear market and industry signals regarding the future trajectory of EV adoption nationwide. The State must take this opportunity to support EV-ready infrastructure and enable Connecticut to lead the way toward an emissions-free transportation sector.

Additionally, local zoning requirements must not act as a barrier to deploying EV infrastructure in residential or commercial structures. Rather, requirements should encourage expansion of EV-ready infrastructure. Parking requirements must take into account the need to support a minimum level of EV charging spaces, as appropriate for the particular building structure. At a minimum DEEP should support building codes that mandate 10 percent of spaces be pre-wired for EV charging. Relating to ADA requirements, the Codes committee need not establish new ADA-compliant requirements; rather, the committee needs only to clarify how EV charging stations should comply with existing ADA requirements.

We support DEEP’s recommendation to consolidate permitting for Level 2 EVSE and DCFC installations. Such permitting would be better streamlined if: (1) applications could be submitted electronically and (2) a schedule of permit prices were published.

- Siting recommendations

While grid impacts should be minimized if and when possible, that should not be the sole determining factor in site selection. Rather, demand and transportation needs should be allowed to shape charging infrastructure location.

- Public charging infrastructure ownership recommendations

The EV Coalition supports DEEP’s recommendation that EDCs be permitted to rate-base make-ready investments in EV supply equipment in appropriate contexts. Utilities are uniquely positioned to encourage development of public EV charging infrastructure. DEEP should advocate in the PURA docket a clear expectation that utilities will submit proposals to support deployment of public EV charging stations.

As discussed further in other sections of these comments, carve-outs to ensure a percentage of EV charging stations are located in low-income and underserved communities are well-intentioned, but may not be the best way to support the transportation needs of these communities. The objective should be to improve access to clean, electrified transportation options that also improve public health, rather than proportional deployment of EV charging stations. Investments in low-income and underserved communities must be tailored to their specific transportation needs. For example, investments in electrified car or ride-sharing services or electrified transit buses may be more beneficial than charging infrastructure for certain communities. Community-specific assessments are necessary to determine the transportation needs of different communities.

Recommendations regarding Consumer Charging Experience, Interoperability, Pricing Transparency, and Future Proofing:

Fostering a positive consumer charging experience is critical to the successful transition to EVs in Connecticut. The challenge in addressing consumer experience through recommendations in the Roadmap is that, because technology is evolving so rapidly in this space, there are risks about being too prescriptive about specific technologies. As noted throughout these comments, the Roadmap should avoid dictating specific technological requirements.

For example, with regard to the proposed requirement that new electrical infrastructure installed at publicly funded DCFC stations be capable of supporting 150 kW charging stations or greater, we appreciate the intent of ensuring future-proofing of investments. However, the Roadmap should be crystal clear that this requirement pertains to the EVSE and not to the chargers themselves. In other words, the “make ready” infrastructure should be future-proofed to support the eventual installation of at least 150kW, but it does not make sense at this time to require actual installation of 150 kW chargers at every DCFC location. With regard to forms of payment, rather than prescribing specific requirements, it is preferable to defer to the existing statutory requirements on this issue found in C.G.S. § 16-19ggg.

With regard to signage and other standardization of charging experience, regional cooperation in this area is important as the region is relatively small with a large amount of cross-border traffic. Driver confusion regarding the availability of charging stations in neighboring states will negatively impact public perception and consumer adoption of EVs.

Finally, we support the draft Roadmap’s recommendation to establish a fine for ICE-ing and authorize state and municipal police and parking enforcement authorities to ticket vehicles in

violation of the law. This is low-hanging fruit and should be adopted. EV charging stations need to be available for EV drivers when needed.

Recommendations regarding Residential and Workplace Charging:

We support adoption of a right-to-charge law prohibiting Multi-Unit Dwellings (MUDs) and condominium associations from restricting lessees or condo owners with designated parking spaces from installing EV charging equipment and associated metering. Relevant stakeholders (e.g., condo owners) should be involved in the legislative process. In other jurisdictions this has led to common-sense approaches that were widely supported.

We further support DEEP’s efforts to ensure that the PURA docket evaluates and addresses approaches to manage EV load, which can take the form of rate design and/or managed charging or demand response programs. Technology needs to be able to support load management.

DEEP should adopt policies to encourage workplace charging in a manner that is technology-neutral and future-proofs these investments. For example, new infrastructure should be able to support L2 charging. The installation cost for L2 wiring is similar to the installation cost of L1 wiring. Thus, there is little value add to wiring only to support L1 charging.

Recommendations regarding Rate Design:

Rate design can be an effective tool for helping to manage EV load, and will be increasingly important as the number of EVs charging in Connecticut continues to increase. We agree with DEEP that if EV-only rates are going to be implemented, it is critical that they not require an additional revenue-grade meter, the cost of which is likely to cancel out the potential savings that an EV owner could accrue through off-peak charging. There are multiple alternatives to second meters to measure the EV component of household load. It can be measured using the embedded metering in smart, networked L2 chargers and advanced household meters that can parse load and identify the EV-specific component. We anticipate that EV load will soon be able to be measured through the communications capabilities of the vehicles themselves. The EV Roadmap should endorse the development of rate designs, including EV-only rate designs, that will help manage EV load. But in light of the rapid technological advances occurring, it is important that the Roadmap not be overly prescriptive about technologies through which EV-only rates can be implemented. The Roadmap should call for the utilities to be taking a proactive role and taking responsibility for managing EV load.

In addition to being a tool for managing EV load, rate design can be critical to removing barriers to deployment of DCFC stations. Demand charges are a major barrier to deployment of public (non-fleet) DCFC. As analyzed by RMI in the context of EVgo’s charging station fleet in California,8 particularly at low levels of utilization, demand charges can swamp volumetric charges under traditional commercial demand rates, thereby undercutting the business case for private installation of DCFC. Demand charges can also pose a barrier to fleet charging, including for depot charging of transit buses. Developing rate designs that address this barrier is critical to enabling deployment of electric transit buses in the state.

The concept of Eversource’s Rate Rider (which shifts the demand charge into the volumetric charge)9, is well-intentioned, but the current language of the Rate Rider is vague and confusing. There are good examples around the country of modifications to traditional demand charges that send appropriate price signals to station owners such as the recently-approved PG&E throughput-based subscription fee approach.10 Ultimately, we recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to designing alternatives to traditional, demand-based rate structures. Each utility will need to design a rate that works best for its service territory. Regardless of the manner by which utilities address this challenge, their respective solutions should (1) be equitable and available to all DCFC, both existing and new, and (2) address the challenge through a predictable, transparent, and sustainable rate design, rather than a short-term incentive.

Recommendations regarding Innovation:

We appreciate the enthusiasm in the draft Roadmap for vehicle to grid (V2G) technology.

In the long term, when EVs are widespread, it will be valuable to be able to harness the stored energy in the batteries of parked vehicles. However, we do not believe that V2G should be identified as a high priority in the final Roadmap. Rather, it is critical in the near term to develop strategies for effective unidirectional smart charging (V1G) management of new EV load.

Recommendations regarding Leveraging Incentives to Promote Equitable, Affordable EV Adoption—CHEAPR Program:

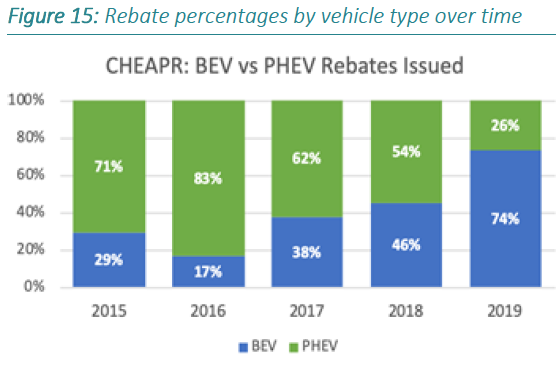

The CHEAPR program has the potential to greatly boost EV adoption. Indeed, studies and modeling show that rebates that reduce the up-front purchase price of vehicles are a strong driver of EV adoption.11 Based on modeling that Synapse Energy Economics conducted for the Sierra Club in New York, it may be valuable to increase the sizing of the CHEAPR rebate for battery electric vehicles.12 Ultimately, the incentives should be sized such that the CHEAPR incentive, in addition to other federal and state incentives, is projected to put Connecticut on track to meet its transportation sector GHG commitments.

Additionally, the CHEAPR program will need to be scaled up to achieve 500,000 ZEVs on Connecticut roads by 2030 in order for the state to meet its climate goals.13 To that end, CHEAPR will need a large and sustainable source of funding. DEEP should explore the possibility of utilizing the Transportation and Climate Initiative (TCI) as a funding source for the CHEAPR program.

DEEP should also evaluate the merits of a low-income adder to the rebate in conjunction with other potential strategies to promote access to EVs for low-income and underserved communities, and extending the low-income rebate to the purchase of used vehicles. One alternative that warrants further consideration is a “cash for clunkers” program similar to what California and British Columbia have developed.

Finally, the EV Roadmap should recommend elimination of the current prohibition on direct sales of EVs, which is stifling sales of EVs in the state. The models that comprise the majority of national EV sales are not being sold in Connecticut. At the same time, the Roadmap should recommend additional incentives for existing auto dealers to increase their sales of EVs. More outreach to dealers regarding the existing CHEAPR dealer incentive is needed, given low levels of awareness by dealers, and additional incentives should be explored, such as: state reimbursement of the percentage of dealership local property tax equal to the percentage of EVs sold by the dealer each year, to a cap of 50%; state waiver of state income tax on all staff salaries based on percentage of EVs sold, to a cap of 50%; reimbursement of 100% of EV charging infrastructure and charging electricity costs at all CT dealer locations; free training for all CT dealers in EV sales using the PlugStarDealer.com program or a similar program; and/or higher CHEAPR rebates for all dealer cars used as service loaners and company cars.

Recommendations regarding Education and Outreach:

We support a coordinated approach to education and outreach among state actors and support a role for utilities and OEMs.

Connecticut should continue to support and participate in the regional Drive Change Drive Electric (DCDE) campaign and the Destination Electric Program to build upon and increase consumer awareness in the state and the region. We support the partnership framework among automobile manufacturers and state governments of the DCDE Campaign. While the campaign provides good web-based resources for learning about electric vehicles, there may be additional opportunities for proactive outreach and promotion. Such opportunities include cross-linking with other relevant state (such as DMV) and municipal (particularly for the Destination Electric program) websites.

We agree that OEMs should (and must) be active participants in advertising and marketing EVs in Connecticut, leveraging their years of experience in promoting conventional vehicles. Among the roles OEMs can play:

- Creation of informational and marketing materials for dealerships. While we assume that OEMs currently do this to some extent, we recommend an expansion of these efforts targeted to EV

- Providing additional dealer incentive for EV

- Providing supplemental consumer rebates for EV Purchases. For example, Nissan has partnered with the CT Green Bank to provide an additional manufacturer incentive of between $2,500 and $5,000 for the purchase of a Nissan Leaf.

- Providing well-promoted community “Ride and Drive” events, in partnership with the state, municipalities, and local businesses.

As noted above, we strongly support the recommendation to conduct focused outreach in underserved communities to inform the development of integrated approaches for deploying electrified transportation services strategically and addressing barriers to EV ownership by low- income households. We emphasize that the deployment of electrified transportation services should be informed by community priorities with respect to the type of services desired, whether that is increased access to light-duty EVs to replace older, unreliable personal transportation or the deployment of more electric buses and other clean transit options, with increased convenience and affordability.

Recommendations regarding Funding Mechanisms to Support Sustainable Incentive and EV Infrastructure Programs—VW EVSE:

VW EVSE expenditures should be coordinated with the utility programs that arise from the PURA ZEV docket.14 DEEP should focus on ensuring that key market segments, such as MUD L2, public transit corridor DCFC, and in-town DCFC, are being addressed.

A portion of the VW funding should be earmarked to support access to electrified transportation for communities that bear an outsize share of transportation emissions. DEEP should conduct outreach into these communities to better understand transportation needs and use VW EVSE funds to support charging infrastructure for transportation programs that will meet these needs (for example, communities that could be better served by car or rideshare programs). This is preferable to simply deploying a percentage of stations in overburdened communities.

Respectfully submitted,

The Connecticut Electric Vehicle Coalition

- Acadia Center*

- Connecticut Fund for the Environment*†

- Connecticut Green Buildings Council

- Connecticut Nurses Association

- Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs*

- Connecticut Citizen Action Group

- ConnPIRG

- Conservation Law Foundation

- ChargePoint*

- Chispa-CT*

- Clean Water Action*

- CT League of Conservation Voters

- CT 350

- Drive Electric Cars New England

- Eastern CT Green Action

- Electric Vehicle Club of Connecticut*

- Energy Solutions, LLC

- Environment Connecticut*

- Greater New Haven Clean Cities Coalition,

- Hamden Land Conservation Trust

- Hartford Climate Stewardship Council

- International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers*

- Interreligious Eco-Justice Network

- New Haven Climate Movement

- Northeast Clean Energy Council

- People’s Action for Clean Energy

- Proton OnSite

- Plug In America*

- RENEW Northeast

- Sierra Club*†

- Solar Connecticut,

- Tesla,

- Union of Concerned Scientists

* Connecticut EV Coalition Steering Committee Membership

Footnotes:

1 CT EV Coalition Feb. 21, 2019 Cmts at 2.

2 Draft Roadmap at 20.

3 Governor’s Council on Climate Change, Building a Low Carbon Future for Connecticut 29-30 (December 18, 2018).

4 An Act Concerning the State Budget for the Biennium Ending June 20, 2021, and Making Appropriations Therefor, and Provisions Related to Revenue and Other Items to Implement the State Budget.

5 See NYSERDA, New York Truck Voucher Incentive Program, available at https://www.nyserda.ny.gov/All- Programs/Programs/Truck-Voucher-Program.

6 See Governor’s Council on Climate Change, Building a Low Carbon Future for Connecticut (December 18, 2018).

7 Energy Solutions, Plug-In Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Cost Analysis Report for CALGreen Nonresidential Update (September 16, 2019), available at: https://caletc.com/energy-solutions-report-finds-that-increasing-the- number-of-electric-vehicle-capable-parking-spaces-at-new-buildings-and-adding-ev-capable-parking-spaces-to- existing-buildings-when-undergoing-certain/.

8 Rocky Mountain Inst., EVgo Fleet and Tariff Analysis Phase 1: California (Apr. 2017).

9 Available at https://www.eversource.com/content/docs/default-source/rates-tariffs/ev-rate- rider.pdf?sfvrsn=e44ca62_0.

10 See PG&E, PG&E Proposes to Establish New Commercial Electric Vehicle Rate Class (Nov. 5, 2018), available at https://www.pge.com/en/about/newsroom/newsdetails/index.page?title=20181105_pge_proposes_to_establish_new

_commercial_electric_vehicle_rate_class; PG&E, PG&E’s Commercial Electric Vehicle Rate (Nov. 20, 2018), available at https://caltransit.org/cta/assets/File/Webinar%20Elements/WEBINAR-PGE%20Rate%20Design%2011- 20-18.pdf.

11 Studies have found a significant increase in EV sales with the implementation of rebates among low- and moderate-income households. Scott Hardman, The Effectiveness of Financial Purchase Incentives for Battery Electric V9ehicles, 80 Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 1110 (2017), https://phev.ucdavis.edu/wp- content/uploads/2017/09/purchase-incentives-literature-review.pdf.

12 Synapse Energy Economics, Inc., Transforming Transportation in New York: Roadmaps to a Transportation Climate Target for 2035 (September 2019).

13 See Governor’s Council on Climate Change, Building a Low Carbon Future for Connecticut 28 (December 18, 2018).

14 PURA Docket No. 17-12-03RE04.

† To whom correspondence should be directed. Josh Berman, Sierra Club. Email Josh.Berman@sierraclub.org or phone (202) 650-6062. Charles Rothenberger, Connecticut Fund for the Environment. Email crothenberger@ctenvironment.org or phone (203) 787-0646, x122.

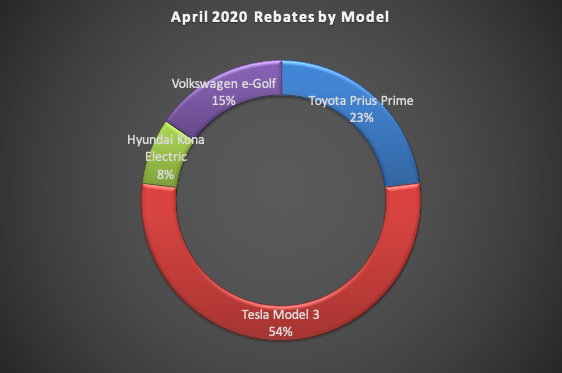

Tesla so dominates the EV market, as well as being the only manufacturer to post a sizable YOY sales increase in Q1, that how many Model 3s are rebate eligible is mostly what determines where the trend goes. It is also possible that some Model 3 supply disruption due to the temporary closure of the Fremont plant is part of the reason, as well. The Model 3 accounted for 54% of April rebates, which translates to all of 7. General Motors has been heavily discounting the Chevy Bolt, but there were no Bolt rebates in April.

Tesla so dominates the EV market, as well as being the only manufacturer to post a sizable YOY sales increase in Q1, that how many Model 3s are rebate eligible is mostly what determines where the trend goes. It is also possible that some Model 3 supply disruption due to the temporary closure of the Fremont plant is part of the reason, as well. The Model 3 accounted for 54% of April rebates, which translates to all of 7. General Motors has been heavily discounting the Chevy Bolt, but there were no Bolt rebates in April.