Driving Electric Is Now a Moral, Fiscal and Climate Imperative

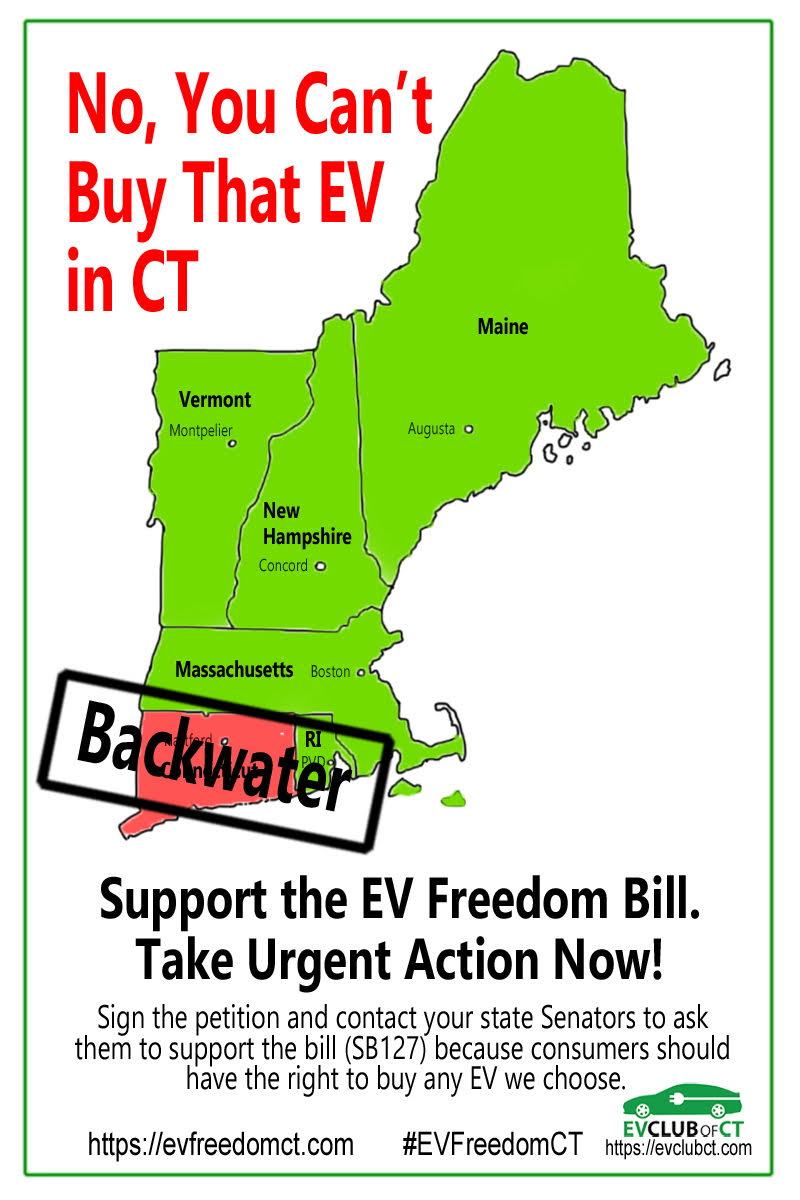

Post by Analiese Paik and Barry Kresch EVs Are Essential to Mitigating the Climate Crisis We’re in a climate crisis and each of us should be taking action, regardless of state and federal policy. Driving … Read more